|

I was able to copy the story. The three photos are added separately.

Long-lost plane may have been found

The Washington Post

1 Aug 2019

BY MICHAEL E. RUANE

On March 18, 1945, Lt. j.g. David L. Mandt took off from Maryland’s Patuxent River Naval Air Station to test out the guns on an experimental fighter plane, the XF8F-1 Bearcat.

Mandt was a veteran aircraft carrier pilot who had flown in battle off the deck of the USS Bunker Hill in the Pacific. He had shot down Japanese planes. He had been on numerous raids on enemy forces. His plane had been riddled in combat.

With World War II turning against Japan, he was back stateside trying out the Navy’s latest fighter. It was the first of its kind, a propeller-driven hot rod with a 2,100-horsepower engine. In photographs, it appeared with the word “TEST” emblazoned on its side.

Mandt, 23, a native of Detroit, took off at 2:15 p.m. and flew out over the glassy surface of the bay.

His plane never returned.

‘A really good view’

The water was unusually clear in the Chesapeake Bay the day diver Dan Lynberg first descended to the bottom to examine the object that had turned up on his sonar survey.

A member of the Institute of Maritime History, a volunteer group of underwater archaeologists, he had gotten the sonar “hit” at a spot east of the air station during a routine survey, he said. He was now going 80 feet down from a dive boat to investigate.

Skilled in “blackwater” diving, where visibility is poor to zero, he was amazed at the day’s clarity. “Got a really good view” of the object, he said.

It was covered in sea growth, fishing debris and a layer of silt, and it seemed to almost be part of

the bottom of the bay.

He could tell it was a single-engine airplane, compact and rugged-looking. He did not recognize the model, “but I could tell by the structure and the wings that it was either a military fighter or aerobatic [airplane], just by the strength that was built into the wings.”

He noticed the engine was torn off the front. The bubble canopy had slid open, and the cockpit was piled almost to the brim with sediment.

But where was the pilot? Did he get out of the plane? Could his remains or effects still be in the cockpit?

“Do not know,” Lynberg said. He tried taking pictures, but they did not turn out. He surfaced and had already noted the location.

That was about 2010, he said. About three years ago, he said, the Naval History and Heritage Command asked institute volunteers to conduct a search for lost aircraft in the bay near the air station. The Navy had begun a systematic search for such planes. One of them was Mandt’s Bearcat.

“We found some unexploded ordnance and that kind of stuff,” Lynberg said. “Then they gave us this box area. They said, ‘We think we lost an F8F out in this . . . area.’ And we went out and searched that area very thoroughly and found nothing.

“Then we thought, ‘Maybe that thing we found a few years ago could be the target,’ ” he said. It was five or six miles from where the Navy believed the plane had gone down, Lynberg said.

“So we went back,” he said. “And with detailed drawings of an F8F, we could go down and say, ‘Yeah. This is it. This is a hit. This is an F8F Bearcat.’ ”

On later dives with the Navy, he said, researchers noted that the shape of the air intakes in the wings, their spacing from the machine guns and the location of a gun camera lens were “a perfect match for a Bearcat.”

In addition, the Navy said Thursday, the bubble canopy was a feature of the plane, and the wingspan of the sunken plane seems to be about 33 feet, 10 inches — close to the Bearcat’s 35-foot wingspan. Experts are not yet positive about the finding.

“We don’t really have that piece of evidence that we need to say conclusively that this is the aircraft that we think it is,” said George Schwarz, an archaeologist with the command.

That could change if divers can excavate the cockpit and find a small metal data plate that bears the aircraft’s bureau number, which is like a car’s vehicle identification number.

In this case, it was 90460. “What we need to do now is go back and send a Navy dive team down,” Schwarz said. “We would try to locate that data plate and then get the bureau number, and then we can say without a doubt it is this specific aircraft.”

The Navy said it hopes to dive on the plane again next spring. And is the pilot still there? “It’s possible,” Schwarz said. “That’s why this site is a little bit sensitive There is a potential for human remains. The pilot was never found.”

The airplane, for its part, was a first. It was the initial model produced, according to the records of Northrop Grumman’s aerospace systems historian. It was built by the former Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. in mid-1944.

Grumman had built the Navy’s earlier Wildcat and Hellcat carrier fighters, and the Bearcat was designed to be more nimble against Japanese fighter planes. It had some stability problems, however, which were apparently worked out, and an odd feature where its wing tips were designed to break off under high stress, aircraft historian Rene J. Francillon said.

The Patuxent River air station, meanwhile, was then the test center for new airplanes, according to the air station’s website. Hundreds of seasoned combat pilots were brought in to try out new models.

Mandt was one of them, and he had seen some stuff.

Over 900 hours in the cockpit

On Nov. 10, 1943, then-Ensign Mandt had taken off from the deck of the Bunker Hill with 26 other Navy planes from fighter squadron VF-18. They were to escort 23 dive bombers and 18 torpedo planes on a strike on the big Japanese base at Rabaul, on the island of New Britain, in the South Pacific.

Mandt was then 22. He had grown up with his younger sister, Patricia, in a small, three-bedroom house on Ardmore Street in Detroit. His father, John, a Navy veteran of World War I, worked as a boring mill operator at an aircraft company, according to government records.

David Mandt had attended nearby Lawrence Institute of Technology and was a member of its “soaring society,” which flew gliders. He earned his private pilot’s license in early 1941.

He had enlisted in the Naval Reserve in March 1942 and was commissioned that November at the Naval Air Training Station in Corpus Christi, Tex., according to the National Archives.

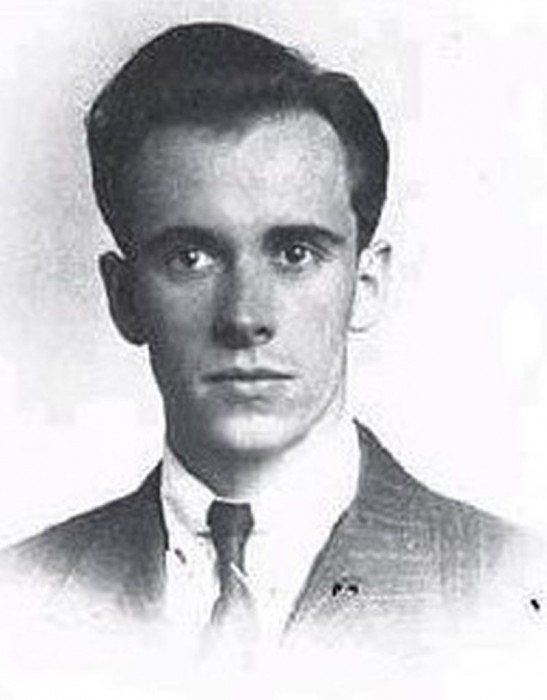

His application for Navy flight training contains a snapshot of a serious-looking young man in a coat and tie. A picture taken for his graduation shows the same young man, now smiling in the white uniform of a naval officer.

Mandt joined squadron VF-18 on Aug. 3, 1943.

Less than four months later, as he and the other American pilots neared Rabaul, they ran into about 60 Japanese fighters guarding the harbor, according to a report in the National Archives posted on the military records website Fold3.

During the ensuing scramble, Mandt and his wingman, Lt. j.g. Jim Pearce, were escorting torpedo planes on their run when a Japanese fighter — a “Zeke” — swooped in behind Mandt and opened fire.

The wings on Mandt’s plane were holed, but Pearce went after the enemy plane and drove it off, according to the report.

The torpedo planes completed their attack. The U.S. fighters picked them up again on the way out.

Suddenly Pearce’s plane was hit by an antiaircraft shell that exploded inside the fuselage. A rudder cable and a hydraulic line were severed. Smoke began to trail from Pearce’s plane.

Mandt began swerving back and forth to cover Pearce and the departing torpedo planes until they reached safe airspace.

Pearce’s plane was so damaged he could barely control it, and he crash-landed when he reached the carrier deck. Pearce survived and went on to become a distinguished test pilot.

Mandt went on to fly for months, helping in attacks on the Japanese at Tarawa, Truk, Tinian and Guam, among other places.

On Christmas Day in 1943, he shot down a twin engine enemy reconnaissance plane near Kavieng, on the island of New Ireland, according to the citation for the Air Medal, which he was posthumously awarded.

Ten days later, he shot down another Japanese reconnaissance plane.

In May 1944, he was detached from his squadron VF-18 and sent to the Patuxent River air station.

He had logged more than 900 hours in the cockpit, most of which were in the hostile skies over the South Pacific.

Out of view

Ten months later, on March 18, Mandt was preparing for his second flight of day, testing the machine guns on the Bearcat.

Far away, World War II was still raging.

For now, he was out of it. He was reportedly engaged to be married, and he had just returned from the wedding of a Navy buddy in New York City.

The wind was light and out of the northeast when he took off, according to the post-accident “crash card.” There was broken overcast at 7,000 feet. The water in the bay was no doubt frigid, as it always is in late winter.

Even though he was a seasoned pilot, he only had about six hours of flying time in the Bearcat.

He was seen to make three successful runs testing the guns, and then his plane passed out of view to the south.

When he had not returned by 3:45 p.m., the Navy sent out search-and-rescue crews. No parachute was found. At 4:45 p.m., the search planes spotted a large oil slick bubbling on the surface. At 5:05 p.m., a boat arrived at the scene and found scattered items floating in the water.

Among them was a left-hand glove. Written on it in ink was the name “Mandt.”

| Attachments: |

Mandt,photo01.jpg [ 214.97 KiB | Viewed 2568 times ]

|

Mandt,photo03.jpg [ 75.8 KiB | Viewed 2568 times ]

|

Mandt,photo02.jpg [ 102.71 KiB | Viewed 2568 times ]

|

|